........INFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYBACHINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITY...........

DATE OF BIRTH: March 21, 1685

PLACE OF BIRTH: Eisenach, Thuringen, (Germany)

MUSICAL ERA: Baroque

ACCOMPLISHMENTS:

1703- Violinist in the chamber orchestra of Prince Johann Ernst

1705- Studies with renowned organist and composer, Buxtenude

1707- Marries his second cousin, Maria Barbara Bach

1714- Becomes concertmaster of the court orchestra in the Court of Duke Wilhelm Ernst

1720- Maria Barbara Bach dies after having 7 children together

1721- Marries Anna Magdalena Wilcken with whom he has 13 children

1723- Moves to Leipzig where he would remain until his death. Here he composes 295 cantatas, 202 of which exist today

July 28, 1750- Dies after an unsuccessful eye operation

MAJOR WORKS: Brandenburg Concerto, Bach's Cello Suites, The Passion of St. John, The Passion of St. Matthew, Art of the Fugue (includes 16 fugues and 4 canons)

........INFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITY...........

Theologian and musicologist Friedrich Smend (1893-1980) presents a theory regarding Bach's use of a number alphabet. This theory is very controversial. Smend claims that Bach uses the natural-ordered number alphabet (A=1 to Z=24) to incorporate words into his music as part of a scheme of number symbolism (Tatlow 1). Many of Smend's claims seem far-fetched. One such claim is Smend's interpretation of the Canon a 4 voce written in 1713 for his second cousin Johann Gottfried Walther. Smend suggests that Bach incorporates his own name in the number of bars, fourteen. B=2 A=1 C=3 H=8 therefore B+A+C+H = 14 (the number of bars). He then suggests that Walther's surname represents the number of notes, eighty-two. W=21 A=1 L=11 T=19 H=8 E=5 R=17 therefore W+A+L+T+H+E+R = 82. Smend takes it one step further by noting that Bach's full name is exactly half that of Walther's. J=9 S=18 B=2 A=1 C=3 H=8 therefore J+S+B+A+C+H = 41 (Tatlow 9). It is unknown whether this correlation has any relevance or if it is merely coincidental.

Smend's number symbolism scheme also suggests that Bach incorporated traditional biblical numbers into his music, including 3 to represent the Trinity, 10 to symbolise the Commandments and 12 to symbolise the apostles (Tatlow 4).

........INFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITYINFINITY...........

Scholars have related the works of Bach to infinity in several contexts, two of which are explored on this site: 1. Figure and Ground and 2. Strange Loops. These concepts are discussed in the Pulitzer Prize winning text written by Douglas R. Hofstadter entitled Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. (For a formal review of the text CLICK HERE)

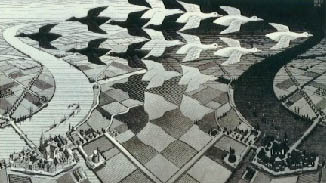

As seen in many of M.C. Escher's works, there is a famous artistic distinction between figure and ground. Hofstadter describes it as such: "When a figure or 'positive space' is drawn inside a frame, an unavoidable consequence is that its complementary shape--also called the 'ground', or 'background', or 'negative space'--has also been drawn" (67). Often less attention is drawn by the background than by the figure; but at times, interest is taken by the background as well. This creates a unique artistic effect as seen in the following examples of Escher:

Hofstadter draws a similar conclusion about figure and ground in music. In terms of music, the melody can be related to the "figure" while the accompaniment correlates with the "background." It is surprising to find melodic lines in our "background" accompaniment. However, in the music of Bach, all lines can act as "figures" (Hofstadter 70). It is possible to find recognizable melodies in that which is generally not considered "foreground." Another figure-ground distinction is found in the difference between on and off beats. By deliberately pushing one melody on to the off beats, Bach can create two, distinct, melodic lines, two "foregrounds." This is particularly evident in Bach's Suites for unaccompanied cello (Hofstadter 70).

![]() Click here for further discussion of Bach's Cello Suites.

Click here for further discussion of Bach's Cello Suites. In the suites, Bach manages to distinguish several musical lines simultaneously

either by means of double-stops (playing two notes at once) or by means

of on-beat/off-beat alteration. At either rate, the ear can separate the

two melodies as they weave in and out. Similar occurences are found in Bach's

Sonatas and Partitas for unaccompanied violin.

In the suites, Bach manages to distinguish several musical lines simultaneously

either by means of double-stops (playing two notes at once) or by means

of on-beat/off-beat alteration. At either rate, the ear can separate the

two melodies as they weave in and out. Similar occurences are found in Bach's

Sonatas and Partitas for unaccompanied violin.

Godel proposes this theory of "strange loops" in regard to both Bach and Escher. With Escher, these "strange loops" are evident in works with a continuous quality--those which seem to have no end and no beginning. Examples include Ascending a Descending, in which soldiers appear to trudge in endless loops, and Waterfall, involving a six step loop.

/climbing.jpg)

MC Escher's Ascending and Descending MC Escher's Waterfall

Godel relates this infinite aspect to music through Bach's canons. For

better understanding of this concept, we must first establish a firm understanding

of a canon. "The idea of a canon is that one single theme is played

against itself" (Hofstadter 8). Copies of the melodic theme are played

by various voices. There are many methods of doing this: in a round-like

fashion staggered by time, in a round-like fashion staggered by time and

pitch, and inverting the melody, among others. To qualify as a canonic theme,

notes must serve a dual purpose: 1. must be part of the melody and 2. must

be part of the harmony. As one can imagine, this is be quite difficult.

Johann Sebastian Bach was a master of this complex musical form. To understand

the relationship between canons and infinity more clearly we /musoffcan5.gif) will examine a

specific example, one which Hofstadter refers to as "an endlessly rising

canon" (10). This canon is simply labeled "Canon per Tonos"

(shown at left) and is found in the Musical Offering. It involves

three distinct voices, the bottom of which sings its theme in the key of

C minor. The middle voice harmonizes a fifth higher, while the top voice

sings the melody. The unique aspect of this canon is that it does not conclude

in the key of C minor, but rather in the key of D minor. This seeming "end"

is not an end at all as the process can be repeated only to "conclude"

with the key of E minor. It appears that this process will continue indefinately

thereby continuing to rise endlessly. However, this is not the case. After

seven successions we find ourselves back in the key of C minor (Hofstadter

10). We have created an endless loop, a "strange loop" as Hofstadter

describes.

will examine a

specific example, one which Hofstadter refers to as "an endlessly rising

canon" (10). This canon is simply labeled "Canon per Tonos"

(shown at left) and is found in the Musical Offering. It involves

three distinct voices, the bottom of which sings its theme in the key of

C minor. The middle voice harmonizes a fifth higher, while the top voice

sings the melody. The unique aspect of this canon is that it does not conclude

in the key of C minor, but rather in the key of D minor. This seeming "end"

is not an end at all as the process can be repeated only to "conclude"

with the key of E minor. It appears that this process will continue indefinately

thereby continuing to rise endlessly. However, this is not the case. After

seven successions we find ourselves back in the key of C minor (Hofstadter

10). We have created an endless loop, a "strange loop" as Hofstadter

describes.

For more information relative to Bach's

canons, click here ![]()

As evident by the manners discussed, Bach truly holds a place in the realm of the infinite. Whether through the number alphabet, figure and ground, or "strange loops," correlations can be drawn which further both our understanding of Bach and of the infinite.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Braid. New York: Basic

Books, Inc., Publishers, 1979.

Tatlow, Ruth. Bach and the Riddle of the Number Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1991.

Works of Escher art compliments of http://www.geocities.com/SoHo/Museum/3828

Left to right: Chris Howard, Chris Lempa, Elizabeth Gamson, Serena Griffin, Mike Lackey

Left to right: Mike Tremblay, Steve McGuinn, Eamon Griffin, Amanda Hakemian, Kevin King

Left to right: Amanda Macomber, Haley Homer

This writing-intensive first-year seminar was based largely on the text by Ira Rosenholtz, Infinity: the Mini-Series. As a portion of the class, Ira Rosenholtz visited Middlebury College as a guest lecturer.

For a personal review of this lecture, click here!

Click here for a personal review of the text!