Russian Gay History

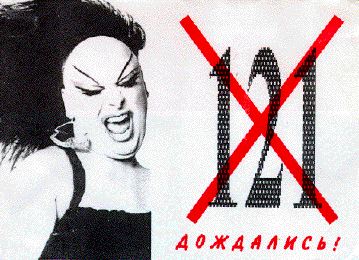

"We've waited long enough!" This was handed out at a gay disco

in May 1993, when Article 121, which criminalized gay sex, was eliminated

from the Russian criminal code.

Medieval Russia was apparently very tolerant of homosexuality. There

is evidence of homosexual love in some of the lives of the saints from Kievan

Rus dating to the 11th century. Homosexual acts were treated as a sin by

the Orthodox Church, but there were no legal sanctions against them at the

time, and even churchmen seemed perturbed by homosexuality only in the monasteries.

Foriegn visitors to Muscovite Russia in the 16th and 17th centuries repeatedly

express their amazement at the open displays of homosexual affection among

men of every class. Sigismund von Heberstein, Adam Olearius, Juraj Krizhanich,

and George Turberville all write about the prevalence of homosexuality in

Russia in their travel and memoir literature. The 19th century historian

Sergei Soloviev writes that "nowhere, either in the Orient or in the

West, was this vile, unnatural sin taken as lightly as in Russia."

The first laws against homosexual acts appeared in the 18th century,

during the reign of Peter the Great, but these were in military statutes

that applied only to soldiers. It was not until 1832 that the criminal code

included Article 995, which made muzhelozhstvo (men lying with men, which

the courts interpreted as anal intercourse) a criminal act punishable by

exile to Siberia for up to 5 years. Even so, the legislation was applied

only rarely, especially among the upper classes. Many prominent intellectuals

of the 19th century led a relatively open homosexual or bisexual life. Among

these were the memoirist Philip Vigel, the explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky,

the critic Konstantin Leontiev, and the composer Peter Tchaikovsky.

The turn of the century saw a relaxation of the laws, and a corresponding

increase in tolerance and visibility. In 1903 Vladimir Nabokov, father of

the writer and a founder of the Constitutional Democrat party, published

an article on the legal status of homosexuals in Russia in which he argued

that the state should not interfere in private sexual relationships. The

period between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917 was the Silver Age in Russian

literature, but something of a golden age for Russian homosexuals. Many

important figures led open gay lives, including several members of the Imperial

Court. Sergei Diaghilev and many of the members of the World of Art movement

and the Russian ballet were gay. In 1906 Mikhail Kuzmin published his semi-autobiographical

coming out novel Wings, which became the talk of the literary world in Russia.

Scholars disagree about the effect of the Bolshevik Revolution on homosexual

rights. Some argue that the Soviets were at the forefront of humanity in

decriminalizing gay sex; others that the Bolshevik asceticism and distaste

for sexuality of any kind set the movement back. In fact, the October Revolution

of 1917 did away with the entire Criminal Code, and the new Russian Criminal

Codes of 1922 and 1926 eliminated the offence of muzhelozhstvo from the

law. Unfortunately, decriminalization in the early Soviet period did not

mean an end to persecution. The modern Soviet fervor for science meant that

homosexuality was now treated as a subject for medical and psychiatric discourse,

an illness to be treated and cured. Furthermore, in the popular mind, homosexuality

was still associated with bourgeois and aristocratic values, with the pre-revolutionary

bohemian elite.

The sexual liberation that accompanied the Revolution was to be short-lived.

The egalitarian and pro-women policies that had liberalized divorce and

marriage laws and promoted abortion gave way by the early 1930s to Stalinist

pro-family policies. It was in this context that the Soviet Union recriminalized

homosexuality in a decree signed in late 1933. As an article by the writer

Maxim Gorky demonstrates, it was also a context in which homosexuality was

connected with Nazism at a time when German-Soviet relations were strained;

Gorky writes, "eradicate homosexuals and fascism will disappear."

Of course, the Nazis themselves criminalized homosexuality only a year later.

The new Article 121, which punished muzhelozhstvo with imprisonment

for up to 5 years, was followed by raids and arrests at the height of the

Stalinist terror. The numbers of men arrested are not known, but by the

1980s there were about 1000 every year. The Soviet Union had the largest

population of incarcerated men in the world, and given the importance of

prison culture for Soviet culture as a whole, it is likely that prison homosexuality

played a part in forming Soviet gay culture. In Soviet prisons there was

a class of men called opushchennye (degraded) who were required to fulfill

the sexual needs of the rest. On the one hand, they were at the lowest rung

of the social ladder, but they were sometimes protected by their lovers.

And not only men charged with Article 121 were opushchennye: any prisoner

could be degraded by ritualized rape -- for losing at cards, over an insult,

or even because his beauty made him an attractive sex object.

Article 121 was often used throughout the Soviet period to extend prison

sentences and to control dissidents. Among those imprisoned were the film

director Sergei Paradjanov and the poet Gennady Trifonov. Threat of prosecution

was also used to blackmail homosexuals into informing for the police and

the KGB. Needless to say, gay men in Russia kept a low profile in the Soviet

period, many restricting their gay activities to small circles of proven

friends. Still, there were some public cruising areas in the larger cities

and one or two bars known to be popular with gay men, though the threat

of arrest or blackmail always loomed. Another threat by the 1980s was the

gangs of gay-bashers who robbed and beat gay men, often with the encouragement

of the police. They knew that if they were brought to court, it was their

victims who would be put in prison.

In 1984 a handful of gay men in Leningrad attempted to form the first

organization of gay men. They were quickly hounded into submission by the

KGB. It was only with Gorbachev's glasnost that such an organization could

come into existence in 1989-90. The Moscow Gay & Lesbian Alliance was headed

by Yevgeniya Debryanskaya, and Roman Kalinin became the editor of the first

officially registered gay newspaper, Tema. Organizations and publications

proliferated. The summer of 1991 saw the first international conference,

film festival, and demonstrations for gay rights in Moscow and Leningrad.

This was followed almost immediately by the attempted coup. Reversion to

a more conservative regime would clearly have threatened their recent gains,

and legend has it that many gay activists manned the barricades protecting

the Russian White House and that Yeltsin's decrees were printed on the xerox

machines of the new gay organizations.

The collapse of the Soviet Union that soon followed the failed coup

only accelerated the progress of the gay movement. Occasional gay discos

were held, more gay publications appeared, gay plays were staged. In 1993

a new Russian Criminal Code was signed -- without Article 121. Men who had

been imprisoned under the article began to be released. Gay life in Russia

today is in the process of normalization. Capitalism has brought the first

gay businesses--bars, discos, saunas, even a travel agency. While life in

the provinces remains hard for gay men, Russian gays in the cities are beginning

to create a community.

Bibliography

This text was prepared for The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality,

2nd Edition, Garland Press.

Back to Russian Gay

Culture

Back to Russian Gay

Culture

Back to Kevin Moss's

Home Page

Back to Kevin Moss's

Home Page