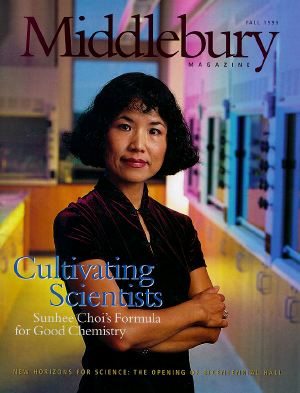

THAT SPECIAL BOND BETWEEN STUDENT AND TEACHER: SHE WORKS THEM TILL THEY'RE RAGGED, COOKS KOREAN FOOD FOR THEM, AND MODELS WHAT IT IS TO BE A WOMAN AND A SCIENTIST BY KIM ASCH FOR ONCE, CHEMISTRY PROFESSOR SUNHEE CHOI found herself at a podium without a story to tell. She was in Oxford, England, at an international conference for researchers of a particular cancer-fighting agent, and her paper was selected as one of the top eight out of 100. All day, scientists had been quoting from "Choi et al" to support their own work, and now they wanted the author to stand in the spotlight and review her findings. Famous among students for her alternately inspirational anec-dotes, passionate lectures, and corny one-liners (i.e., science is pHun), Middlebury chemistry department's diminutive dynamo was momentarily speechless. Understandable. The other seven papers to receive such distinction originated from big research universiti es, as is almost always the case. "Choi et al" was the only ranking project to come out of a liberal arts college and to list undergraduates as coauthors. "I wasn't prepared for it," she says, still savoring that moment of glory before 300 of her peers last March. "I told them, this work is all done by undergraduates." Lots of ears should have been tingling back on campus, because right then someone in the audience piped up, "Let's all congratulate Middlebury undergraduates!" and there was a rousing round of applause for Choi's student collaborators. "They are so famous:' Choi says. "They are my pride."

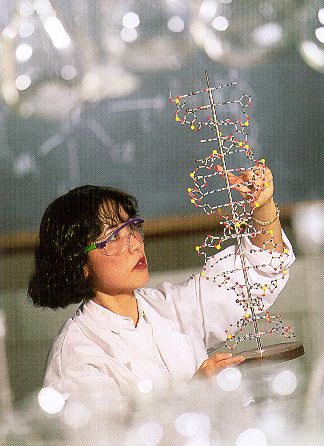

It's summer and she is -In break in her gutted office in what is left of the old science department. Soon, she will embark on a fresh semester in the spectacular, new Bicentennial Hall, but right now, Choi is busy teaching a course to high school students who have shown an interest in chemistry and Middlebury. She is just the person to turn them on to both. In the classroom, as in the lab, she's a maestro. Tan, fit, and perfectly attired in a red, sleeveless tunic, matching cotton mini, and chunky sandals, the colored chalk is her baton as she writes out complex chemical formulas on the blackboard. In staccato English (Korean is her first language) she tells the story of these letters and numbers and how they come together to fight cancer. She calls this research project her "Opus No. 7." "My team is a symphony orchestra;' she says, referring to her student researchers. "We use tons of instruments. I am the conductor. We do biochemistry, organic chemistry, inorganic chemistry." Thanks to two grants over a six-year period totaling $222,000 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Choi and her students are conducting basic research on the mechanism of anticancer activity of the platinum(IV) compound. The platinum compound has been shown to be toxic to tumors that are resistant to cisplatin, the most popular anticancer drug. Understanding how platinum(IV) compounds attack cancer cells should lead to the development of improved chemotherapeutic drugs, Choi says. Pointing to a diagram of cancerous DNA being attacked by the fearsome cisplatin, she is radiant: "Isn't it beautiful?" In May, all five graduating seniors who majored in straight chemistry were women, four of them Choi's advisees. Over the course of her 12 years at Middlebury, she has bonded with many of her undergraduate colleagues. She and husband Jim Larrabee, a chemistry professor and associate dean of the faculty, continue to socialize with alumni, attending their weddings, medical school graduations, and dinner parties. More often, they invite former students over to their house for feasts of Choi's favorite Korean foods or Larrabee's famous chicken wings. But this group of women majors is special to Choi because she feels so strongly about steering women toward careers in science. She is relentlessly proud of her female proteges, adding her own spin to a slogan she picked up from actress Goldie Hawn. "Women can do 400 things," the superstar told Good Housekeeping magazine. "Women scientists can do 401 things," Choi asserts. Every chemistry major is required to read biographies of Marie Curie, the Polish-born physicist who, with her French husband Pierre Curie, shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for physics with Henri Becquerel for the discovery of radioactivity. "My students tease me that I try to turn all of them into Marie Curie:' she says. Not exactly, but she does require that they "try to be the best scientists and the best citizens, like Marie." It can be tough living up to what Choi deems is your best. "Basically, she expects you to know everything," says Sarah Delaney '99, who just started working toward her Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech. Amy Kinner '99, now in her first year in the master's/Ph.D. program in environmental health science at UCBerkeley, agrees, "She's definitely more rigorous than most. Sunhee definitely expects a lot of us. She would give us a quiz at the end of class on the material we had just been taught to make sure we were paying attention." Choi's physical chemistry course is known as the crucible of the major; if you can make it through that, you'll survive to graduate. Joanna Wolkowski '99, who will enter Yale's Ph.D. program in chemistry next year after taking a break to help coach Wellesley's basketball team, remembers the nearly insurmountable standards Choi set for them and how she helped them achieve more than they ever thought they could. At one point during the semester, Wolkowski and her classmates complained that the workload was so overwhelming, they weren't getting enough sleep. The students dragged themselves into class, rumpled and in sweats. Choi, as always, was dressed to the nines.

The conductor decided the struggling orchestra needed more rehearsal time. First, she began holding review sessions over lunch. Then, she added Sunday meetings at her home. She cooked them dinners and shared stories about her days as a student in Korea and then at Princeton, where she met her husband. Soon, her students began reciprocating with dinner invitations. Wolkowski, who emigrated from Poland in 1986, made traditional foods from home. Shwe Mon '99, now in the Ph.D. program for chemistry at Johns Hopkins University, cooked Burmese meals. In socializing with their mentor, the students observed a Renaissance woman in action, balancing the demands of raising two children with her passion for chemistry and her extracurricular pursuits such as hiking, gardening, cooking, classical music, and clothes. "She's got to be the best-dressed professor at Middlebury," Delaney says. "I think part of her attitude is, you get up in the morning, get dressed up, put on your make-up, and when you get to class it'll help you focus." Back in the summer classroom, Choi is drawing a picture for the high school students to help them understand why basic research is so important. She's no artist. "What am I trying to draw?" she quizzes the class. "An elephant?" the teens guess, giggling. Choi explains that cancer is like the elephant, and researchers are Eke the blindfolded little stick figures she draws in a circle around it. All are trying to get a picture of what's in front of them by examining one little portion. They have to share information with each other to know it's an elephant. That's why basic research and collaboration are so important, she says, because understanding the little pieces and how they fit together will lead to big answers. Choi is a firm believer that perseverance in life, as in the lab, achieves results. "I have worked so hard to get anything in my life. That's my karma, I think," she says. "When I get a grant, somehow I have to work two or three times as hard. I'm a foreigner, my English is so bad, but I get it." If anything, her imperfect English endears her to students, who are relieved to find a flaw. Wolkowski and Delaney sometimes fall into what they call "Sunhee speak," and Wolkowski's basketball teammates picked up on it, too. At the end of a practice, they would bid each other good-bye the Sunhee way, "Ya!Ya! See you tomallow!'' Choi is never very far away from her students. Wolkowski remembers tutoring a group of underclassman for her Introduction to Chemistry course one night and getting stuck on a problem. "There was no hesitation, we would call her at home if we needed her help," she says. One particular night, Choi was giving one of her famous dinner parties when Wolkowski called. "She came over in a dress with a big sweatshirt over it and these huge boots-because it was raining of Korean food," she recalls. "I think it didn't bother her at all because I think she's so dedicated. She wanted to make sure we really understood the material." When the time came to apply to graduate school, Choi insisted they only apply to five. "You get into every one," she told them. "Best to make decision sooner rather than later." The girls laughed and rolled their eyes. "She was always dropping names of the best schools," Delaney recalls. "We were like, yeah, whatever." As it turned out, each of the five women went on to good graduate schools. Suzanne Muchene '99 is pursuing a master's of public health in epidemiology at Boston University. MIT and Caltech fought over Delaney. Kinner is at Berkeley. Mon is at Johns Hopkins. Wolkowski applied to University of Chicago, Northwestern, Princeton, and Yale and was amazed to learn she'd been accepted at each. Only Choi was unfazed. "She's just very confident in our abilities," Wolkowski says. "More than we are in ourselves." Kim Asch is a writer living in Burlington, Vermont. |